Written by: Hurin Hasana Binti Hasnan & Yew Jun Huo

Edited by: Jinghann Hong & Shameeta Masilamany

As climate change intensifies, countries worldwide faces growing risks from floods, sea-level rise, droughts, and other climate-related hazards. Adaptation is thus increasingly critical, where ‘adaptation’ refers to adjustment in natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities (UNFCCC, 2025). In 2023, the 28th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in Dubai established the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience, a strategic initiative guiding national and international efforts to plan, finance, and implement adaptation measures. This coincided with the historic achievement of the US$100 billion annual climate finance goal, including record allocations to the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund for Least Developed Countries, signaling a renewed global commitment to scaling climate action (UNEP, 2023).

Adaptation finance, broadly defined as funding intended for adaptation activities, has thus emerged as a key component of both global and national climate strategies (UNFCCC, 2020). Flows come from a mix of international entities—such as UNFCCC funds, multilateral development banks, the Adaptation Fund, and the Green Climate Fund—alongside bilateral and multilateral channels and domestic budget allocations. Despite this, the UNEP Adaptation Gap Report estimates an annual adaptation finance gap of USD 187–359 billion, indicating that public budgets alone will not suffice (UNEP 2024). Evaluations of UNFCCC-funded adaptation projects indicate that about half of these projects are either unsatisfactory or unlikely to be sustainable without continued funding, highlighting systemic challenges in ensuring long-term resilience (UNEP, 2023).

For Malaysia, this context emphasizes the urgency of not only allocating adaptation finance but also spending it strategically to maximize resilience. This article examines Malaysia’s existing adaptation expenditures, before drawing lessons from countries such as Malawi, Singapore, and the Netherlands.

Malaysia’s federal expenditure on climate adaptation

In Malaysia, adaptation options range from technological solutions (e.g., enhanced sea defenses or flood-proof houses); to individual behavior changes (e.g., conserving water during droughts); as well as early warning systems for extreme events; improved risk management and insurance mechanisms; and biodiversity-based approaches (e.g., nature-based solutions such as mangrove restoration to protect communities from storms). Despite increasing adaptation actions, the pace remains insufficient relative to the scale of climate threats.

Recognizing the critical role of adaptation finance, Malaysia has received substantial international support to strengthen its climate resilience. The country was awarded EUR2.8 million from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) to support the development of its National Adaptation Plan, providing a strategic framework for addressing climate risks at the national level (NAP Global Network, 2025). At the regional level, Penang Island has secured USD 10 million from the Adaptation Fund to implement a nature-based climate adaptation programme, demonstrating the potential of locally tailored interventions (Adaptation Fund, 2022). In addition, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) has contributed approximately USD 124 million directly through GEF Grants to support climate adaptation across various sectors, further bolstering Malaysia’s capacity to mitigate climate impacts and build long-term resilience (Global Environment Facility (GEF), n.d.).

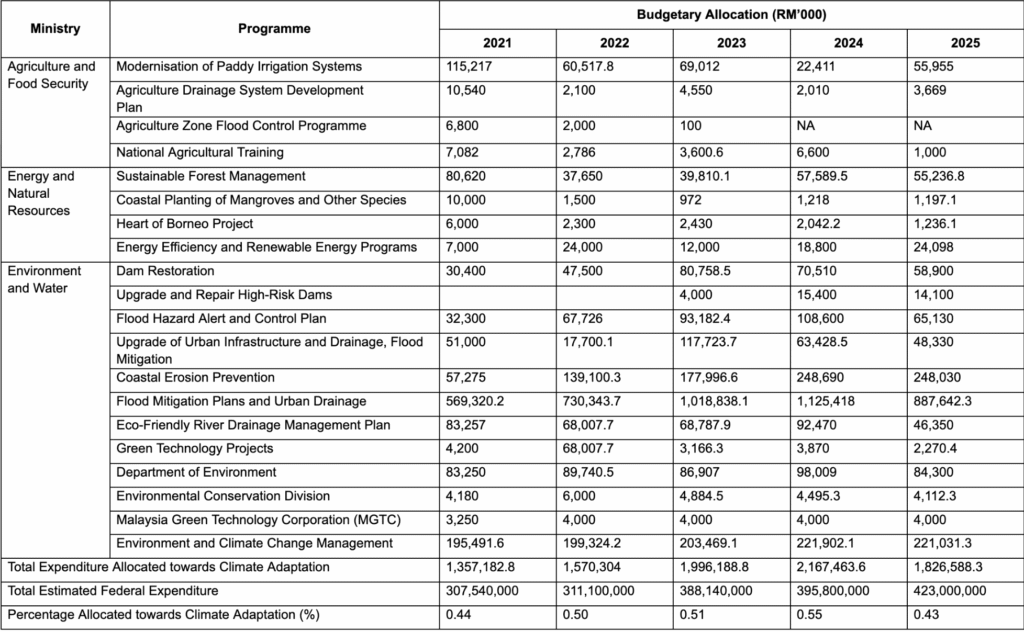

With the growing prioritization of climate adaptation finance, it is important to observe how Malaysia has historically allocated its budget in this regard. Table 1 below exhibits the estimated federal expenditure towards climate adaptation in the past 5 years (Budget Portal Ministry of Finance, 2025). While trends indicate a focus on water management, flood mitigation, and ecosystem-based solutions, it is worth pointing out that limited climate tagging in national budgets further complicates the visibility and tracking of adaptation programs (Mahadi & Joshi, 2023).

Overall, data suggests a strong emphasis on water-related resilience between 2021–2024. Funding for flood management remained consistently high, with Flood Mitigation and Urban Drainage Plans dominating the allocation within Environment and Water, peaking at over RM 1.12 billion in 2024. Coastal Erosion Prevention funding shows a steady increase, reaching RM 248 million in both 2024 and 2025. Dam Restoration and Flood Hazard Alert Programs also received substantial but more variable funding, peaking in 2023–2024 before declining slightly in 2025.

Meanwhile, energy transition programs have recently seen increased allocations. Investments in Green Technology Projects and the Malaysia Green Technology Corporation (MGTC) remain relatively stable in recent years, with MGTC consistently receiving RM 4 million from 2022 onwards.

Table 1. Malaysia Budgetary Allocation for Climate Adaptation Programmes (2021-2025) (Authors, 2025)

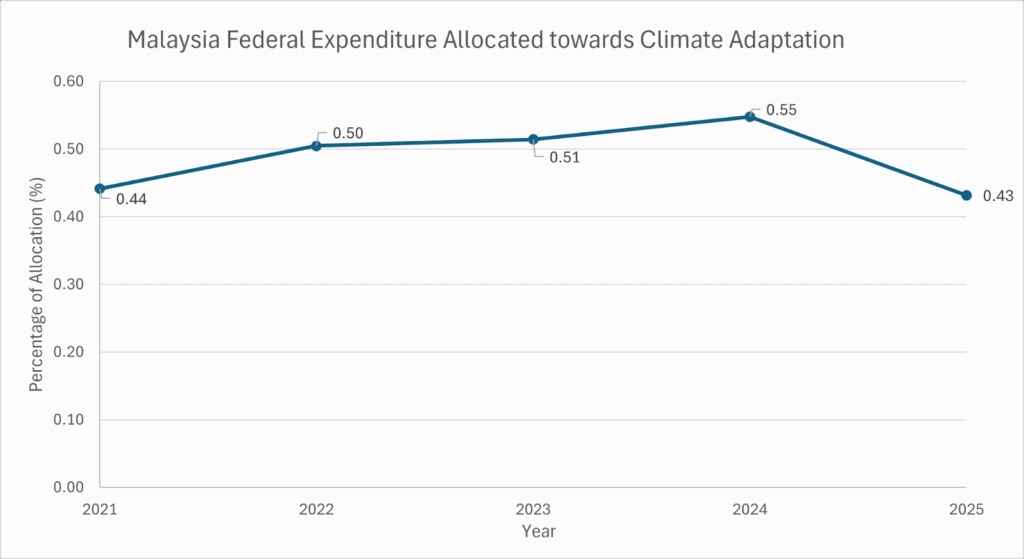

Figure 1 summarises the data above to indicate the trend in climate adaptation allocations.

- Total federal expenditure on climate adaptation increased steadily from 2021 to 2024, rising from RM 1.36 billion in 2021 to RM 2.17 billion in 2024.

- There was a slight decline in 2025 to RM 1.83 billion, possibly due to program completion, budget revisions or shifts in priorities.

- As a share of total federal expenditure, climate adaptation funding remained below 1%, peaking at 0.55% in 2024 before dropping to 0.43% in 2025. This highlights a potential gap in funding relative to growing climate risks.

Figure 1. Trend in Percentage of Malaysia’s Budget Allocated for Climate Adaptation Programmes (Authors, 2025)

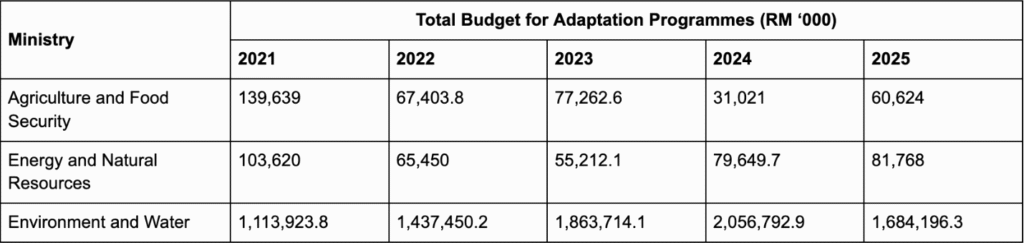

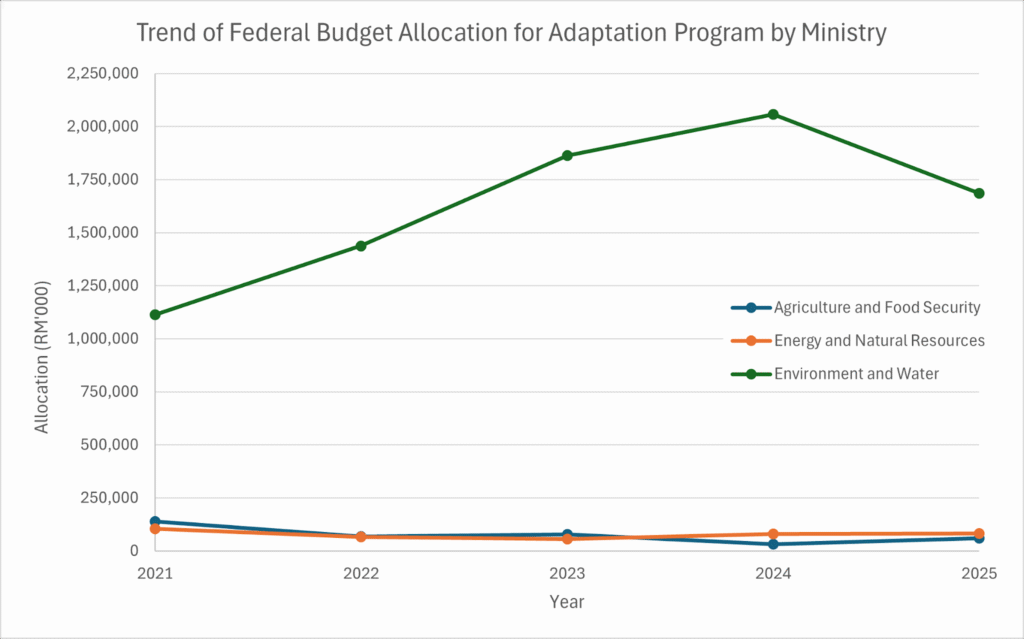

The contribution of ministries to climate adaptation also varies. Table 2 and Figure 2 summarizes the budget allocated by each ministry from 2021 to 2025. The Ministry of Environment and Water consistently received the largest share of adaptation funds across all years, with allocations rising from RM 1.11 billion in 2021 to RM 2.06 billion in 2024, then slightly decreasing in 2025. The Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security and the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources received significantly smaller allocations, though the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources saw some growth in energy efficiency and renewable energy programs.

Table 2. Ministry-Based Budget Allocation for Climate Adaptation Programmes (2021-2025) (Authors, 2025)

Figure 2. Trend in RM ‘000 of Malaysia’s Budget Allocated for Climate Adaptation Programmes by Ministry (Authors, 2025)

Note: The ministries responsible for adaptation also shifted during this period. Initially, Energy and Natural Resources were managed separately from Environment and Water. They were combined into the Ministry of Natural Resources, Environment, and Climate Change from 2023 to 2024, before being separated again in 2025 into the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability and the Ministry of Energy Transition and Water Transformation to increase administrative efficiency and allow deeper focus within the respective ministries (Ismail, 2023).

Lessons from around the world

Singapore: Climate adaptation finance and investment opportunities

Singapore, a low-lying island city-state, faces urgent climate adaptation challenges, with sea-level rise projected to reach 1.15 meters by the end of the century (Singapore National Climate Change Study, 2024). Coupled with high tides and storm surges, estimates suggest that one-third of Singapore could be vulnerable to coastal flooding. Recognising these risks, Singapore’s two largest asset owners, GIC and Temasek, managing a combined US$1.1 trillion in assets, are increasingly treating adaptation solutions as investment opportunities (ThinkSpace, 2025).

Both funds note that climate adaptation remains historically underfunded compared to mitigation, as financing adaptation efforts was traditionally seen as a state’s responsibility. While GIC also highlights that many adaptation solutions contribute to both resilience and mitigation outcomes, making it difficult to sharply separate the two, both ultimately conclude that climate adaptation is a significant and complementary investment theme alongside decarbonisation.

GIC, in collaboration with Bain & Co., estimates the climate adaptation market could grow from US$2 trillion today to US$9 trillion by 2050, including sectors like weather intelligence, flood-resistant building materials, indoor cooling systems, and water storage solutions.The fund stresses the importance of an interdisciplinary approach that blends scientific evidence with industry expertise, given the complexity and variability of adaptation standards and taxonomies

Temasek, in partnership with BCG, highlights private equity’s role in bridging the adaptation finance gap, potentially growing to US$0.5–1.3 trillion annually by 2030 (Temasek Sustainability Report, 2025). The report highlights opportunities in both early-stage, pure-play adaptation companies, which carry higher risk; and established firms where adaptation represents a smaller but growing portion of their business. It also underscores the potential for localized adaptation solutions to scale globally, as demonstrated by wildfire management services expanding beyond North America in response to rising wildfire events worldwide.

Malawi: Shifting away from reliance on international funds

Least developed countries often face unique adaptation challenges compared to their developing and developed counterparts. Malawi, which has previously experienced severe floods, exemplifies a nation in urgent need of climate resilience. Malawi’s National Climate Change Investment Plan (2013-2018) highlights efforts towards environmentally sustainable practices, detailing its governance structures, regulatory frameworks, and investment priorities (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2013).

In a presentation for the 2019 SADC, Malawi emphasized its reliance on international funding to support these initiatives (UNFCCC, 2019). Most recently, Malawi received USD 37 million from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) for climate projects across 6 climate-vulnerable districts (Ministry of Health – Malawi, 2025).

Reliance on international funding can provide short-term support. To reduce its dependence on international funding for climate adaptation, Malawi initiated the establishment of a National Climate Change Fund in 2019 that is currently used to manage domestic and international climate funds received (NDC Partnership, 2025). Nonetheless, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Climate Change remains committed to driving adaptation efforts and building its national resilience (Ministry of Natural Resources and Climate Change – Malawi, 2025).

Netherlands: Self-sustained climate resilience

The European Union’s consistent progress in climate initiatives offers valuable lessons for Malaysia. The Netherlands, for example, established the Dutch Fund for Climate and Development (DFCD), a national fund supporting climate adaptation and mitigation projects. Backed by the government and partner organizations, the DFCD provides financial support to emerging climate initiatives in developing countries. Some notable projects include the development of climate-resilient agriculture in Nepal and the recycling of biomass waste to produce tableware in Pakistan (SNV, 2025; WWF, 2023)

As a developed country, the Netherlands is able to independently fund its adaptation efforts, unlike developing countries that largely rely on international support. Interestingly, this financial autonomy opens doors for adaptation projects that are not held to the conditions of the available international funds, but rather, are driven by their government’s own policies on climate change resilience (Erbach & Dewulf, 2024).

Concluding thoughts on Malaysia’s climate adaptation journey

Malaysia’s efforts to strengthen climate resilience face several systemic challenges that must be accounted for during planning and distribution of adaptation finance (UNEP, 2023):

- Equitable distribution of adaptation finance: Vulnerable groups, such as coastal communities, rural populations, and Indigenous peoples, face disproportionate climate risks, and ensuring funds reach those most in need remains a persistent challenge.

- Long time horizons for adaptation benefits: Interventions like resilient infrastructure, ecosystem restoration, and nature-based solutions often take years or decades to yield full protective benefits, which can be complicated by uneven political commitment and inconsistent financing.

- Bureaucratic complexity and transparency: Ambiguity in decision-making processes (especially around who determines funding priorities and beneficiaries), delays in fund disbursement, and limited oversight can slow implementation and hinder accountability. The need for stronger transparency in how adaptation funds are allocated and monitored is widely acknowledged, as robust oversight is essential to build public trust and accountability.

- Institutional and regulatory capacity: A work in progress for Malaysia, who is still developing the institutional frameworks needed to enforce adaptation standards and ensure project quality. There is the on-going need to align national initiatives with international best practices.

Malaysia’s climate adaptation journey highlights the importance of complementing mitigation with robust adaptation measures to address both current and future climate risks. While decarbonisation remains essential to limit future climate impacts, adaptation measures are equally critical to safeguard vulnerable communities, ecosystems, and the economy from the adverse effects already being felt. Moving forward, Malaysia should prioritise equitable and transparent financing, strengthen institutional capacity and regulatory oversight, and foster public-private collaboration to scale up adaptation solutions. By doing so, the country can build a more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable future in the face of escalating climate challenges.

Water is a fundamental element for life on Earth, covering nearly 71% of the planet’s surface and sustaining all living organisms. From the Milo ais we drink to the rice we grow, from powering industries to keeping ecosystems in balance, water shapes the way we live every day.

At the same time, water connects us deeply to the natural world, reminding us just how important it is to protect and manage it wisely. (Who hasn’t sat under a waterfall, enjoying the torrent of pitter-patter splashes on your back?)

In Malaysia, water is also at the frontline of climate adaptation. Too little or too much of it can disrupt lives, livelihoods, and in its most unpredictable, wipe away entire communities. In this 4-part series, we dive into the story of water in Malaysia and it relates to the climate and environment.

If you’re interested in…

- Understanding the issue of too little water (water scarcity), click here.

- What happens when there is too much water (sea level rise), click here.

- What happens in response to flooding (early warning systems), click here.

And to tie it all together, we take a look at the state of adaptation finance (here) in Malaysia.