Written by: Nur Batrisyia Binti Isna Elias & Damia Munira Bakhthiar

Edited by: Jinghann Hong & Shameeta Masilamany

Water is an indispensable resource, essential for all living beings on Earth to survive. Yet, water insecurity—the inability to access adequate, safe, reliable, and affordable water for human and economic well-being (Tallman et. al, 2022)—remains a global challenge. Water insecurity issues include issues of inadequate supply such as scarcity, drought, and irregular rainfall (Tallman et. al, 2022).

Despite being a tropical country blessed with abundant rainfall, Malaysia is not immune to this crisis. Seasonal droughts, water pollution, and rising demand are creating deficits in national supply. In particular, droughts are influenced by monsoonal variability and El Niño events, both of which are being intensified by climate change (Risam & Jamaludin, 2023).

At the same time, heavy reliance on freshwater resources makes the country highly vulnerable to pollution from improper waste disposal and direct effluent discharge into rivers and lakes, as seen in the Sungai Kim Kim incident in 2019 (BBC, 2019). This poses a threat to the already diminishing water supply, adding to the water insecurity issue faced.

Meanwhile, water demand continues to rise due to population growth and rapid urbanisation, which puts pressure on across sectors, including industry, agriculture, and households (Rashidi, 2025). Water supply disruptions as seen in Klang Valley (Raihan et. al, 2023), Penang (Bernama, 2025), and Sabah (Chong, 2025) particularly over the last several years illustrate the fragility of Malaysia’s water supply.

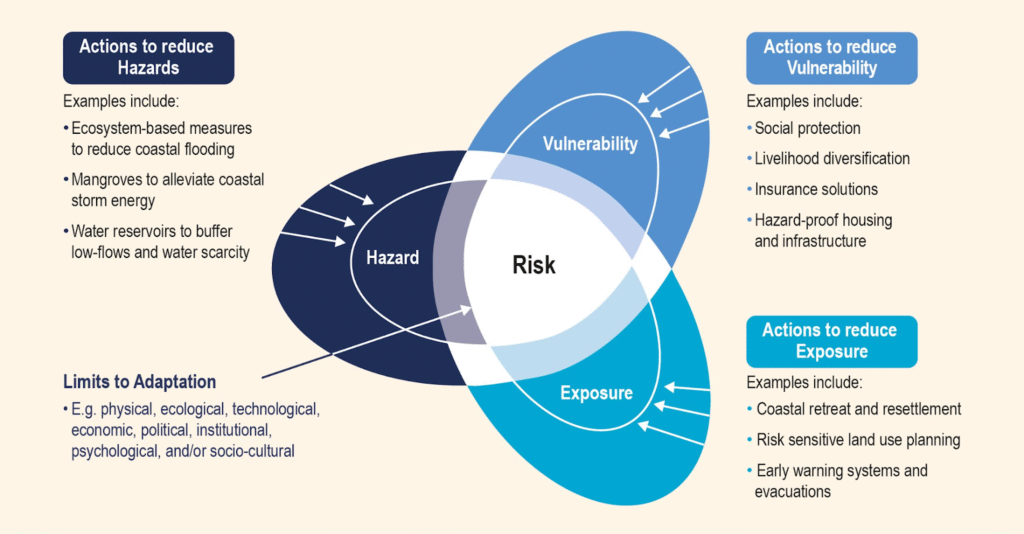

To better understand water scarcity challenges, this article applies the IPCC AR6 risk framework, which defines risk as the interaction of three components: hazard, exposure, and vulnerability. This approach allows us to move beyond viewing water insecurity as a matter of rainfall or supply alone, and instead examine the layered risks shaping Malaysia’s water future.

Understanding water scarcity through IPCC lens

Most Malaysians are used to thunderstorms and flooded streets, making the idea of water insecurity seem almost ironic. Yet, as the thousands lining up for tanker trucks in Klang Valley know, having rain does not guarantee reliable, clean water from the tap.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) frames risk as the interaction of three components: hazard, vulnerability and exposure.

- Hazard: The potential occurrence of the natural or human-induced event that may cause harm (e.g., droughts). Hazards are typically characterized by their intensity, frequency, and spatial extent.

- Exposure: The presence of people, infrastructure, ecosystems, or assets in places that could be adversely affected by hazards (e.g., urban residents dependent on a single water source).

- Vulnerability: How sensitive those exposed people, infrastructure, ecosystems, or assets are, and how well they can cope and adapt. It depends on social, economic, environmental, and institutional factors (e.g., low-income households cannot afford alternative water sources or storage).

This framework emphasizes that reducing risk can be achieved by reducing vulnerability, reducing exposure, or mitigating hazards, rather than focusing solely on the hazard itself. Mathematically, risk (R) is often conceptualized as:

Risk=f(Hazard, Exposure, Vulnerability)

The image indicates options for risk reduction through adaptation, where adaptation can reduce risk by addressing one or more of the three risk factors (vulnerability, exposure, and/or hazard). (IPCC, 2014)

a) Hazard: the physical threat to water

The first layer of risk involves the physical events that disrupt water availability.

| Hazard | Brief explanation |

| Drought and shifting rainfall | Malaysia’s rainfall is mainly influenced by the Northeast monsoon (Nov–Mar). Studies show delays and shortened wet seasons, leading to hydrological and meteorological droughts (Wang et al.,2016; Suhana et al.,2023). In the 2014-2015 drought, the Sungai Selangor Dam dropped below 40% capacity, triggering widespread rationing (TheStar, 2014). In 2021, approximately 3000 households in Kedah were without water as a result of the state’s drought (Free Malaysia Today, 2021). In the same region three years later, Kedah’s rice bowl region had to delay planting due to irrigation shortages, affecting food security (TheStar, 2024; The Straits Times, 2024). |

| Saline intrusion and groundwater depletion | In coastal states like Kelantan and Johor, over-extraction of coastal groundwater has caused saline intrusion that contaminates aquifers (Kamal et al., 2020; Zulkifli et al., 2025). Similar issues in Jakarta have caused land subsidence and saltwater intrusion (Abidin, H. Z, et al. 2011). The image below illustrates how groundwater extraction shifts the freshwater‑saltwater interface landward, allowing saline intrusion into previously fresh aquifers. Saltwater wedge intrusion model (Kyra H. A et al., 2024) |

| Pollution and infrastructure failures | In addition to climate-driven hazards, water pollution and aging or damaged infrastructure further threaten the reliability and safety of Malaysia’s water supply. Incidents such as the Sungai Kim Kim chemical spills in 2019 forced school closures in Pasir Gudang and created major public health risks (The Strait Times, 2019; The Borneo Post, 2019). Ammonia contamination in Sungai Langat (2014) forced the Batu 11 (Cheras) and Bukit Tampoi treatment plants to shut down, affecting millions (Ithnin, H., 2014; MalayMail., 2014). Emergency responders in protective suits conducted cleanup operations along the Sungai Kim Kim (The Straits Time., 2019) Additionally, floods which frequently damage pipes, pumps and treatment infrastructure further compound risks (Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM)., 2022; Rosmadi et al., 2023) |

b) Exposure: who and what is at risk?

The second layer of risk encompasses the people, infrastructure, ecosystems, or assets whose lives and livelihoods are directly affected by water scarcity. The examples below illustrate some cases but are not exhaustive.

| Exposure | Brief explanation |

| Urban and industrial centres | As economic hubs, Klang Valley, Penang and Johor Bahru drive Malaysia’s GDP. However, with high population density and massive industries, it faces surging water demands. For example, the Klang Valley (2020) odour pollution events forced the closure of all Sungai Selangor Phase 1, 2, 3 and Rantau Panjang treatment plants, impacting over 1 millions residents (New Strait Times, 2020). |

| Agriculture | Farmers in Kedah (especially those under the Muda Agricultural Development Authority) as well as in Sabah and Kelantan (under Kemubu Agricultural Development Authority) depend heavily on consistent irrigation. During the 2024 El Niño, droughts caused yield losses of 30-40%, directly threatening food security (The Star., 2024; NADMA., 2024; HarakahDaily., 2024; MalayMail., 2024). Though Malaysia has yet to come to this extreme, it is worth noting that other consequences of low yields can include forced migration, as seen in India’s Maharashtra areas which face similar climate-driven risks (International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED)., 2021; Centre for Development Policy and Practice (CDPP)., 2024). |

| Rural and indigenous communities | Indigenous communities and rural households often lack reliable piped water, where their way of life is directly reliant on rivers or rain-fed water tanks. During dry periods, they face water shortage and in some cases must buy water and depend on intermittent deliveries to meet basic needs, leaving communities vulnerable (Bernama., 2023; Kamu et al., 2024; Source, 2024; Borneo Post., 2025). |

c) Vulnerability: limitations in system and society

The third layer of risk refers to how susceptible a community, region, or ecosystem is to harm from the lack of sufficient water.

| Vulnerability | Brief explanation |

| Institutional and governance factors | Malaysia’s water management is spread across multiple, overlapping agencies (Department of Irrigation and Drainage (DID), Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Air Negara (SPAN), Lembaga Urusan Air Selangor (LUAS), Kementerian Peralihan Tenaga dan Transformasi Air (PETRA), etc), which may lead to fragmented planning, slow crisis response, and unclear accountability (MalaysiaKini., 2019; Ahmed, M et al., 2023; ). Malaysia currently lacks a fully integrated national water security strategy with effective real-time data sharing, which can hamper real-time response and long-term planning (Integrated Water Sector Data Centre (IWSDC -Volume III)., 2022). |

| Socioeconomic factors | Rural and Indigenous communities remain underserved, while awareness of and water-saving practices are not widely adopted (Michaela L. G et al., 2023; Source, 2024). It can be said that there is low adaptive capacity, as awareness of climate-driven risks is limited, reducing societal resilience. |

| Technical factors | Malaysia’s non-revenue water (NRW; water lost through physical losses, commercial losses and operational losses) stands at 36% nationally in 2021 (The Edge Malaysia., 2023). Physical Losses: Leaking or burst pipes, often decades old.Commercial Losses: Water theft and faulty meters.Operational Losses: Maintenance-related issues Non Revenue Water is calculated as the difference between the (A) volume of Treated clean water produced and (B) the volume that actually reaches end users (MalaysiaKini., 2021; Air Selangor., 2022) |

Concluding thoughts

Traditional discussions of water security often focus on supply and demand. The AR5 framework broadens this view, showing that Malaysia’s water insecurity is not just about rainfall, but about how physical threats, the systems they affect, and society’s ability to cope interact. Breaking down Malaysia’s challenge with water insecurity using this framework reveals where action can be effectively directed.

In February 2022, the IPCC released its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), which introduces a fourth dimension—response—in understanding climate risk (IPCC, 2022). Responses to water insecurity can be short-term, such as water rationing, rainwater harvesting, recycling, awareness campaigns, and emergency preparedness; or long-term, including integrated water resource management, diversification of water sources, infrastructure upgrades, and capacity building for farmers.

This emphasises that understanding risk is inseparable from how we act to reduce it. Now more than ever, framing water insecurity through this comprehensive lens is critical: it guides effective action, strengthens resilience, and safeguards Malaysia’s economy, public health, and environmental sustainability.

Water is a fundamental element for life on Earth, covering nearly 71% of the planet’s surface and sustaining all living organisms. From the Milo ais we drink to the rice we grow, from powering industries to keeping ecosystems in balance, water shapes the way we live every day.

At the same time, water connects us deeply to the natural world, reminding us just how important it is to protect and manage it wisely. (Who hasn’t sat under a waterfall, enjoying the torrent of pitter-patter splashes on your back?)

In Malaysia, water is also at the frontline of climate adaptation. Too little or too much of it can disrupt lives, livelihoods, and in its most unpredictable, wipe away entire communities. In this 4-part series, we dive into the story of water in Malaysia and it relates to the climate and environment.

If you’re interested in…

- Understanding the issue of too little water (water scarcity), click here.

- What happens when there is too much water (sea level rise), click here.

- What happens in response to flooding (early warning systems), click here.

And to tie it all together, we take a look at the state of adaptation finance (here) in Malaysia.