Written by: Nurafiqah Mohd Sahar & Yew Jun Huo

Edited by: Jinghann Hong & Shameeta Masilamany

Malaysia’s battle with flooding has intensified in recent years, with devastating floods becoming increasingly common across the country. While floods have historically been seasonal during the northeast monsoon (November–March), changing climate patterns are increasing both the frequency and severity of flood events. In December 2021, the country experienced its worst flooding in decades, displacing over 71,000 people and causing economic losses of approximately RM 6.1 billion (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2022).

Malaysia faces three main types of flood hazards:

| Type of flood | Image explanation (Rosenzweig, 2024) |

| Fluvial flooding The east coast states of Kelantan, Terengganu, and Pahang experience severe monsoon-driven river flooding annually between November and March. | |

| Pluvial flooding Urbanising areas like Kuala Lumpur, Penang, and Johor Bahru, where development outpaces infrastructure, are increasingly affected by flash floods due to impervious surfaces and inadequate drainage (Department of Irrigation and Drainage, 2021). | |

| Coastal flooding As a peninsula with extensive coastlines, parts of Malaysia also face growing coastal flood risks as climate change drives sea level rise. Find out more about coastal flooding here. |

Early warning systems (EWS), typically installed in river basins and flood-prone areas, serve as the first line of defence by providing crucial lead time for evacuation and preparation. This article focuses on flood early warning systems and mitigation strategies across Peninsular Malaysia, highlighting state-level approaches, challenges, and innovations. The discussion below first outlines Malaysia’s federal- and state-level EWS, followed by a state-by-state analysis of systems, strengths, and gaps.

Note: While recent flooding events in Sabah are acknowledged, East Malaysian states are not covered in detail due to the timing of drafting (before the flooding event) and subsequent limited author capacity.

Introduction to flood mitigation in Malaysia

Malaysia has developed multiple flood mitigation strategies at both federal and state levels, primarily led by the Department of Irrigation and Drainage (Jabatan Pengairan dan Saliran, JPS) under the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability (NRES). JPS spearheads the Integrated Flood Management (IFM) programme, which combines multiple strategies to mitigate flood risks, combining structural, non-structural, and technology-driven approaches (DID Malaysia, 2023).

Key national initiatives include:

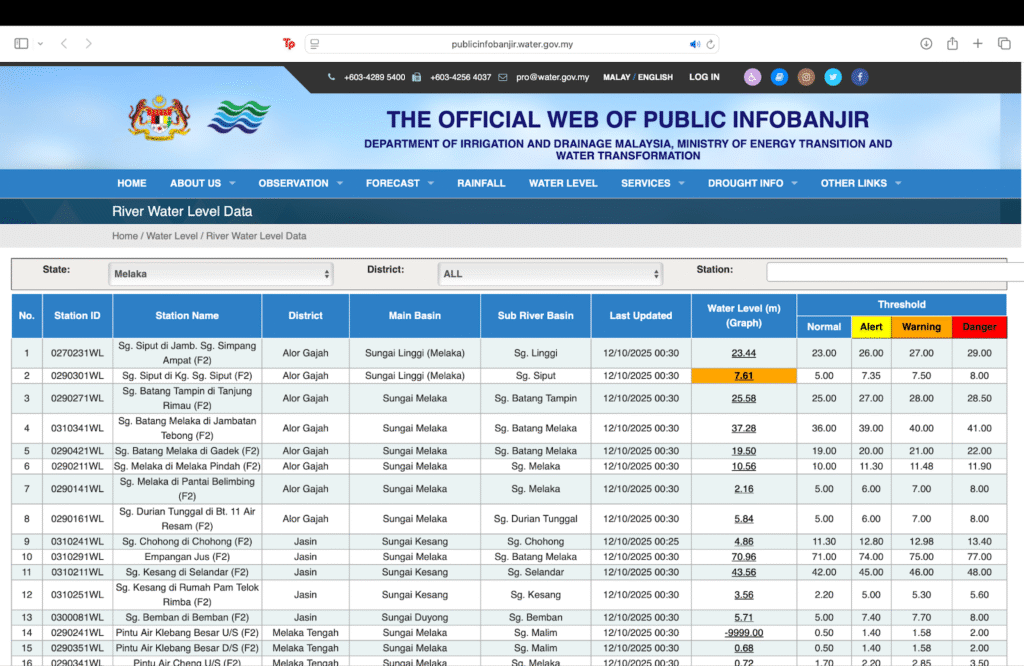

- Infobanjir (e-Banjir): National-level EWS that provides real-time rainfall, river level, and flood forecast data (JPS, 2023). The data is collected via a network of hydrological and meteorological stations nationwide and visualised through interactive maps and dashboards

- Integrated Disaster Management System (IDMS): Consolidates disaster-related data, including satellite imagery, to provide decision-support tools for government agencies during flood events (NADMA, 2022). Managed by the National Disaster Management Agency (NADMA).

- Sistem Informasi Amaran Banjir (SIAB): Disseminates flood alerts via SMS, sirens, and local community networks, particularly in rural areas. (JPS, 2020).

Figure 1. Screenshot of Infobanjir, showing Melaka’s River Water Level Data as of 11.10.2025 (Source)

At the state level, adoption and technological sophistication vary:

- Kuala Lumpur & Selangor: Advanced forecasting systems with smart sensors, SCADA integration, and predictive modelling. The SMART tunnel in KL diverts floodwaters away from urban areas while maintaining traffic flow (Entura, 2007)

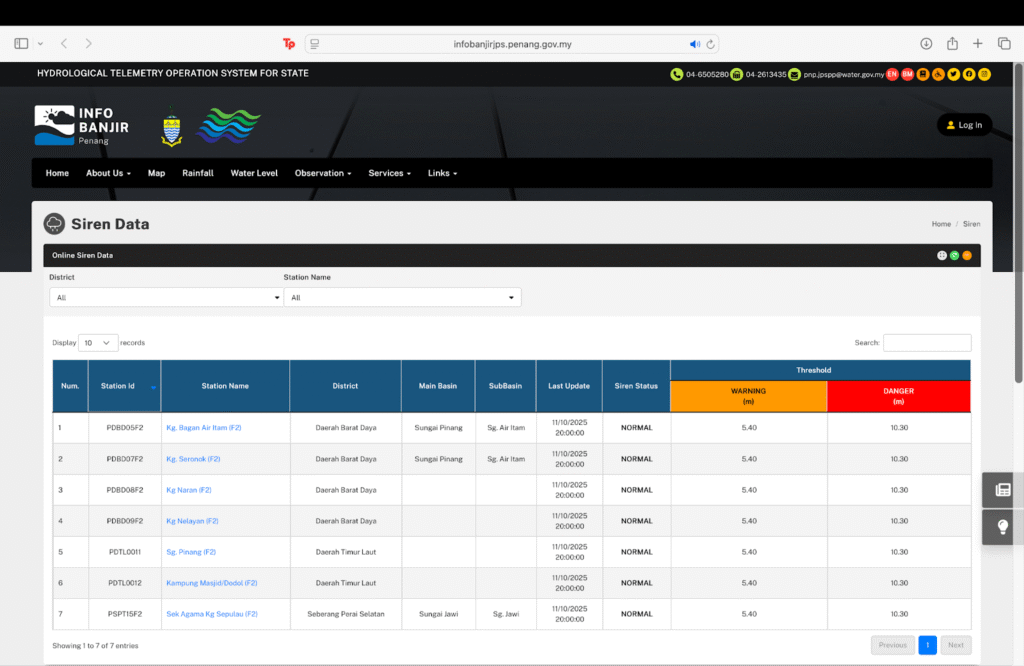

- Penang: 25 siren stations and water-level sensors are being upgraded with a smart disaster app for real-time alerts and automated malfunction reporting (Tan, 2019).

- Kelantan & Terengganu: Systems rely more on manual monitoring, river gauges, and SMS alerts, with strong community engagement through programmes like KARIB (Chan et al., 2021).

Despite these advances, challenges remain. Key gaps include limited interoperability between federal and state systems, uneven technical capacity, and the need for stronger community-based early warning dissemination, particularly in rural and indigenous areas.

Between 2006–2020, Malaysia allocated approximately RM15 billion for flood mitigation, yet recurring flood events suggest gaps in implementation and effectiveness, including in flood forecasting and warning programmes (Bank Negara, 2024). Moving forward, enhancing public-private partnerships, improving data transparency, and investing in climate-resilient infrastructure will be vital to strengthen Malaysia’s early warning capabilities (UNDRR, 2023).

Different types of early warning systems in (Peninsular) Malaysia

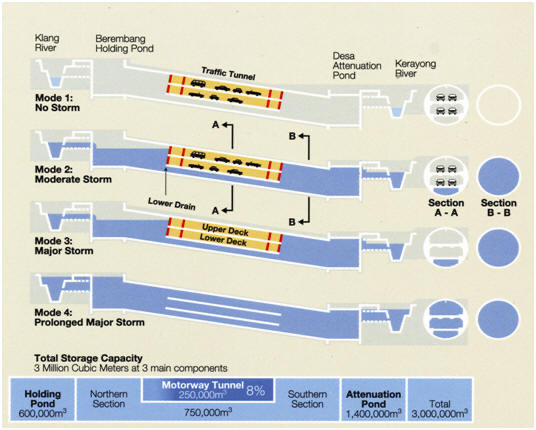

Developed in response to the city’s recurring flood events, Kuala Lumpur’s Stormwater Management and Road Tunnel (SMART) project was designed to protect the city centre while also serving as a dual-purpose traffic tunnel. This innovative design has reduced the frequency and impact of flash floods in Kuala Lumpur, delivering substantial cost savings by mitigating potential flood damage to government assets, businesses, and city infrastructure.

Figure 2. Different modes of the SMART tunnel (Source)

At the core of SMART is a flood detection and warning system that collects real-time rainfall and streamflow data through a network of strategically placed monitoring stations. This data feeds into an integrated hydrological and hydraulic modelling system that simulates flood behaviour across the catchment, including river reaches and the tunnel infrastructure itself. With a 45-minute lead time, the system can forecast storm characteristics and predict flood inflows, giving operators time to clear traffic and activate full flood diversion.

Operations are further supported by a Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system, which refreshes forecasts every five minutes by combining live data with hydrological and hydrodynamic models. This enables timely, data-driven decisions and rapid switching between traffic and flood-control modes. During extreme rainfall events, the tunnel can be fully converted for flood control, diverting stormwater away from vulnerable urban areas and discharging it safely downstream.

In Selangor, existing physical flood mitigation infrastructure, which includes flood retention ponds, pump houses, floodgates, and dual-function reservoirs already exist. Selangor is rolling out a technology-driven, integrated flood warning system as part of its long-term strategy designed to move the state from reactive to proactive disaster management (Bernama, 2025). Led by the Selangor Department of Irrigation and Drainage (JPS) with support from the Federal government, central to the smart design is the deployment of water level monitoring stations, flood simulation models, risk mapping tools, and automatic alarms. The system, expected to be operational by 2026, will enable automatic alerts and predictive insights to help residents and authorities prepare in advance, thereby reducing risks to lives and property.

Similarly, Penang’s flood warning system currently relies on 25 siren stations (11 on the island and 14 on the mainland) and water-level sensors in flood-prone areas, supported by pump houses and manual alerts. However, the state is now moving toward a more inclusive, technology-driven approach. Future plans include a smart disaster management app, GPS-based alerts, automated SMS warnings, and an integrated online platform that consolidates data from the Department of Irrigation and Drainage (JPS), the Penang Island City Council (MBPP), and the Seberang Perai City Council (MPSP). These upgrades aim to overcome existing challenges, particularly fragmented data and the lack of automated reporting for equipment malfunctions, while ensuring that both Penang Island and Seberang Perai benefit from timely, community-centred early warnings (Tan, 2019).

Figure 3. Screenshot of Infobanjir, showing Penang’s siren data as of 11.10.2025 (Source)

In Kelantan, the River Basin Flood Forecasting and Warning System relies on a network of river gauges, rainfall stations, and manual monitoring, with flood alerts disseminated mainly through SMS. Terengganu has developed an integrated flood warning system that combines river telemetry from 28 automated river level stations at major waterways including Sungai Terengganu, Sungai Dungun, and Sungai Kemaman, with manual gauges, traditional sirens, and community announcements. Strong community response networks is a defining feature of both states’ strategies, with programmes such as KARIB under the national Program Ramalan and Amaran Banjir (PRAB) enabling culturally appropriate communication and local engagement.

The systems in Kelantan and Terengganu highlight the importance of community-based approaches, but also underscore the technological gap compared to more data-driven systems in the above states. In Kelantan and Terengganu, the EWS remains limited in automation and predictive modelling, with delays in transmission in remote areas and coverage largely confined to major river basins, leaving urban areas less well served. This provides only short lead times for advance warnings, constraining its effectiveness during extreme events.

Figure 4. Website screenshot of Amaran Banjir (PRAB), which is run by Ecotourism & Conservation Society Malaysia (Source)

The Kemaman Community Flood Resilience Programme in Terengganu emerges as a notable example of effective local flood management during the 2014 floods. A study published in IntechOpen highlights how important it is that residents are active participants rather than passive recipients of warnings, where the community’s proactive engagement significantly reduced flood impact in Kemaman compared to other similarly affected areas (Othman et al, 2018), This programme trained local volunteers to monitor conditions, maintain simple warning equipment, and coordinate evacuation plans, all of which enhanced the community’s ability to respond promptly, in doing so reduce response time.

Concluding thoughts

Malaysia can enhance its flood warning capabilities through emerging technologies by integrating AI and IoT, which could address current system weaknesses by combining data from river sensors, rainfall patterns, tidal information, and satellite imagery. While technological solutions offer tremendous benefits, they must be implemented thoughtfully to avoid potential negative consequences. Over-reliance on automated systems without adequate backup measures could create vulnerability during power or communication outages, and these systems should be designed with accessibility for all populations in mind.

Strengthening Malaysia’s flood early warning capabilities requires a balanced approach that combines emerging technologies, community engagement, and effective governance. By tackling technological, social, and institutional dimensions together, Malaysia can build a comprehensive and resilient early warning system capable of protecting its citizens from increasingly frequent and severe flood events.

State-by-State High Level Comparison (Authors, 2025)

| State | Existing system | Strength | Weakness |

| Kuala Lumpur (SMART tunnel) | SCADA-integrated, real-time rainfall & streamflow sensors, hydraulic/hydrological modelling | Dual-purpose tunnel reduces urban flood risk, strong predictive modelling | Limited to city centre/SMART catchmentNot scalable to other areas |

| Selangor | Flood retention ponds, pump houses, dual-function reservoirs; water level sensors & simulation models | Planned innovations are proactive instead of reactiveFederal-state collaboration and large budget allocations for flood control | Data integration is still developing; current systems are project-specificScalability and maintenance of large infrastructure may present future challenges |

| Penang | 25 siren stations and water-level sensors in flood-prone areas | Planned digital integration that covers both island & Seberang Perai | Data fragmented across JPS, MBPP, and MPSP; no single integrated real-time platform yetExisting siren/sensor systems lack smart features for auto-reporting malfunctions |

| Kelantan | River gauges, rainfall stations, manual monitoring, SMS alerts | Culturally appropriate, strong local engagement | Limited automation, fewer advanced sensors, minimal predictive modelling Covers mainly major river basins but limited urban coverageDelayed transmission in remote areas |

| Terengganu | 28 automated river level stations and manual gauges; traditional sirens and community announcements | Established community response networkRecent partnership with telecommunications providers | Less technological integration, with minimal real-time data processingShort lead times, less effective during extreme events |

Water is a fundamental element for life on Earth, covering nearly 71% of the planet’s surface and sustaining all living organisms. From the Milo ais we drink to the rice we grow, from powering industries to keeping ecosystems in balance, water shapes the way we live every day.

At the same time, water connects us deeply to the natural world, reminding us just how important it is to protect and manage it wisely. (Who hasn’t sat under a waterfall, enjoying the torrent of pitter-patter splashes on your back?)

In Malaysia, water is also at the frontline of climate adaptation. Too little or too much of it can disrupt lives, livelihoods, and in its most unpredictable, wipe away entire communities. In this 4-part series, we dive into the story of water in Malaysia and it relates to the climate and environment.

If you’re interested in…

- Understanding the issue of too little water (water scarcity), click here.

- What happens when there is too much water (sea level rise), click here.

- What happens in response to flooding (early warning systems), click here.

And to tie it all together, we take a look at the state of adaptation finance (here) in Malaysia.